Jesus Christ was certainly onto something when he said: “Blessed are those who have not seen, and yet have believed.” (John 20:29).

This is the central idea not just of Christianity but of many of the religions that humanity has elaborated over the past 10,000 years or so: in the absence of conclusive, indisputable evidence of a divine entity, people must suspend disbelief and have faith.

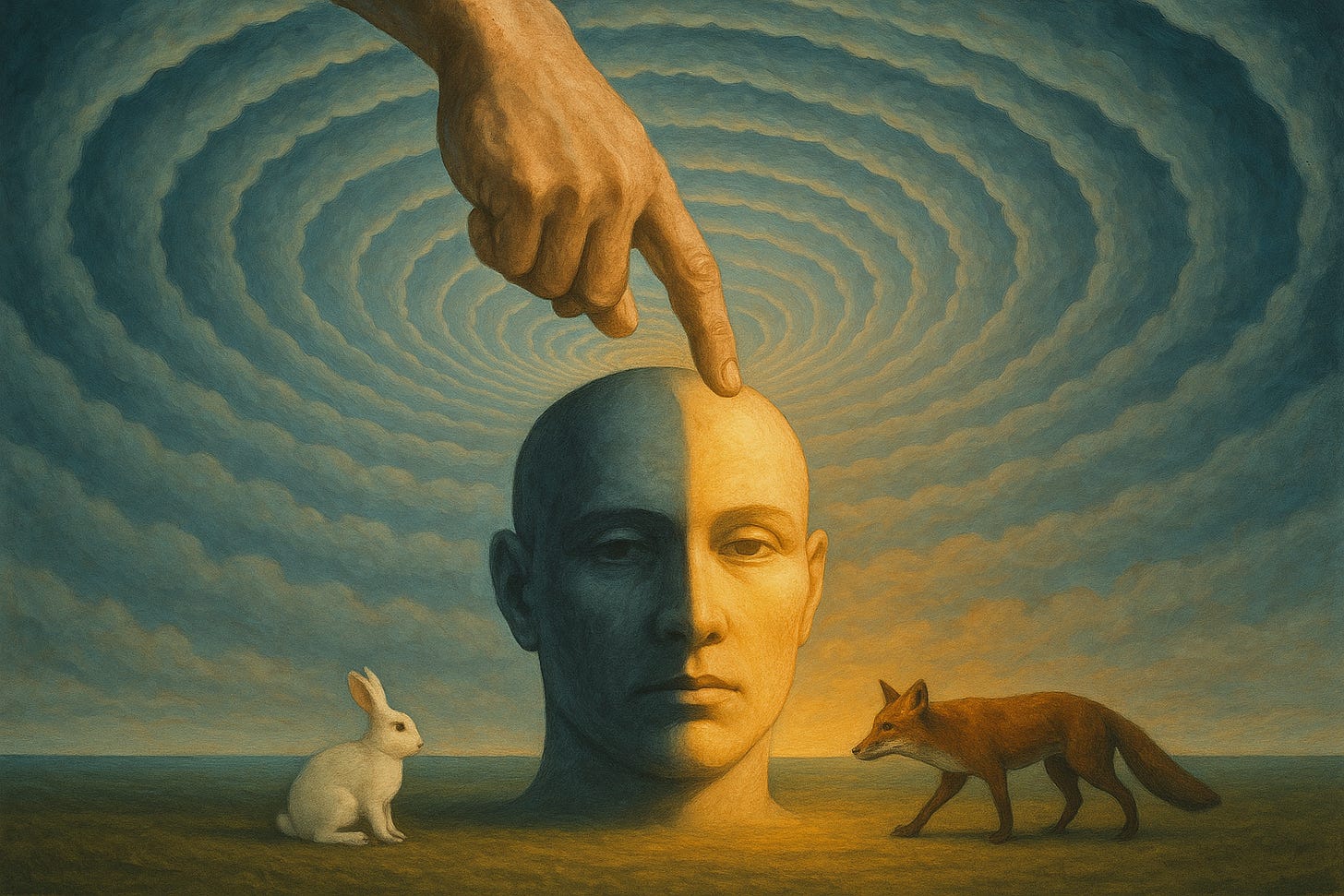

But does it do them any good? Is religion an antidote for - or a vaccine against - mental distress? Does trust in God make living easier - like believing that there is a safety net down below you as you cross the threadbare tightrope of life?

Just how “blessed” are those who “yet believe”?

It’s something I have wondered about, on and off, for years. As a child, I sat in church a lot, dicing with boredom and feeling a certain serenity, particularly as I sang with other people. I listened to the stories and sermons about lives saved by faith, about people whose Damascene conversions ended their anguish.

But I was also aware of the suffering of those in the pews around me, forsaken souls with depression, anxiety, and other forms of human misery.

In what way were they “blessed”?

Was faith helping them?

Or was it the other way round: their lives were so painful that they sought relief and meaning in a spiritual experience. If this was the case, then surely religions would over-index on mental illness?

With the big monotheistic religions all celebrating major moments in their calendars, it seemed a good time to explore the question, so I decided to dig out the research and see if there are any answers. (NB: I do understand that religious belief is a personal thing, and I’m not trying to prove or disprove the existence of God. Just to answer that specific question: can faith ease mental distress?)

*

Fortunately, there is no shortage of academic research on the overlap between religious faith and mental wellbeing. Unfortunately, it is not terribly conclusive.

Researchers have identified some potential benefits, pinpointing three main reasons: social support and welfare (religious communities tend to look after their own), cultural togetherness (sharing the same beliefs as other people is reassuring) and meaning (people are able to make sense of setbacks like bereavement, illness, suffering, unfairness, inequality, catastrophe). 1 2

Researchers have also found that spirituality can result in neurological change 3. Others suggest benefits are limited to participation in public religious events. 4 Meanwhile, some research found no benefits at all. 5

I asked Dr Dan Major-Smith, a researcher at Bristol university, to walk me through the paths of research-ousness, and answer the question: does faith really heal?

“The answer is not particularly straightforward,” he said, in a remark that any cleric would have been proud of. “Religious beliefs may help individuals suffering with mental health problems - for instance if you believe that God has a plan for you, this may aid when coping with stressful life events.”

On the other hand, he added, religious beliefs could be problematic “if individuals feel that God or some other divine power is punishing them, or has abandoned them.”

I asked Dan about the reverse effect - whether people with troubled minds might be more likely to turn to spirituality for succour. He said that, yes, some people might indeed search for meaning and solace in churches and synagogues and temples and mosques. But others with depression and anxiety might be more like to withdraw socially and avoid religious services.

In general he said: “The empirical research on this topic is rather contradictory and difficult to interpret. For instance, many studies have reported a correlation between religion and better mental health, but the majority of studies are from the US, meaning results may not generalise to other societies.”

“Plus, there’s the old adage that ‘correlation is not causation’, meaning that it’s very difficult to establish whether religion causes better mental health (or vice versa) from these studies.”

His own study looking at communities in southwest England published in March6 found no strong evidence in either direction: “A change in religiousness seemed to have little impact on people’s mental health, while a change in mental health had little impact of people’s religiousness.”

But he adds: “Just because on average there seems to be little relationship between religion and mental health, that does not mean that religion might not be beneficial for some individuals coping with mental health problems.”

All of which leaves me with one last question. What about the absence of religion? Over the past 150 years, the rise and rise of science and rationalism, the horror of total war, the comfort of materialism and the decline of the sacred have combined to decimate once popular faiths.7

Does this godlessness have an effect on our collective psyche? Has it changed the way people feel about themselves and the lonely world we inhabit? Is the decline of religious institutions, with their very mixed track record of civic support and appalling abuse, a good thing? Or has something been lost along the way, a sense of humility, identity, belonging and respect?

I’d love to know your thoughts on this so get involved in the comments. Here is a tune I wrote a few years ago to get the ball rolling.

I’m away next week. Back here in a fortnight.

https://pure.rug.nl/ws/files/120348641/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10508619.2020.1729570

https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSNewsShow.jsp?ID=433

This is really interesting. I have often had people say to me that my Christian faith is “just a crutch to cope with life.” While my faith does give me huge peace, it also can make life difficult in a world that is, as you say, turning towards a scientific approach to life.

Thank you for considering the role of faith and spirituality, an often overlooked but crucial part of the picture for many of us. I really appreciate it!